|

| New England whalers like the one above sailed Alaska waters in the 1800s. |

Novelist and UAA professor Don Rearden received INNOVATE funding this year to support research for his latest creative endeavor, a novel about whales that traverses the three great epochs of Alaska whaling history – pre-contact, commercial whaling of the 1800s, and modern-day subsistence whaling under the governance of the Alaska Eskimo Whaling Commission.

“The good thing about getting this award is that it allowed me to say, ‘I have this project I am working on, and the university is sponsoring me,' ” Rearden says.

That support helped him secure a Scholar in Residence position for a week this summer at the

New Bedford Whaling Museum in Massachussetts, where he begins gathering some of the historical detail that will color his work.

Why a novel for such an epic history? And, frankly, is there room for another after Melville’s

Moby-Dick? And just how gutsy was it to go after INNOVATE funding for creative writing in a competitive field choked with scientists anxious for laboratory research space and time.

Rearden says that for the most part, he chose fiction because the documentary non-fiction work on whaling already had been done. He cites John Bockstoce and his 1986 work from University of Washington Press,

Whales, Ice & Men: The History of Whaling in the Western Arctic, among others.

But the idea of a fictionalized history had been alive in him for some time. For one thing, he and close friend and colleague Shannon Gramse had tossed around the idea of a screenplay that would cover Alaska’s great whaling eras. He’s moving ahead on a novel because the story is just so big, he says, and novels reach a wider audience than screenplays. And besides, “We’ll probably still do a screenplay once the novel is done,” he says. And he hopes to convince poet Gramse to provide some poems for the novel.

Power of story

But for Rearden, there is an even more personally compelling reason to choose fiction over non-fiction. In his view, it contains the power of story – elements of character, voice and predicament that can reel an audience in -- right through to the last page.

|

| Herman Melville |

Certainly Melvillle knew that, and yes, his famous

Moby-Dick intimidates Rearden.

“That’s an amazing work, so yes it’s scary,” Rearden acknowledges. That’s why Rearden plans to give Melville a nod right upfront in his own novel.

But Rearden brings something unique to this Northern whale writing adventure. His boyhood spent in rural Alaska with his schoolteacher mother and law-enforcement dad exposed him to the hold that an active spirit life can have among villagers. He found it magical and life changing.

He arrived in Akiak as a second grader. And while some of the boys were compelled to box him about when he first arrived, he found village life not just satisfactory, but wholly engaging. He was thrilled to be out riding dog sleds and learning how to set fish traps under the ice.

But, even more, there were the mythical stories everyone told, “…that idea of ghosts and spirits -- this other world that is just really real for everyone.” Remote communities then had fewer distractions … “we had just one phone in the whole village,” he remembers. The spirits and monsters that peopled local stories thrived, and quickly turned Rearden into a serious student of the culture.

Even in elementary school, he knew he would be a storyteller. “I read a lot. And even before I could be, I knew I wanted to be a writer.”

His family returned to his birth state, Montana, but they were back in Alaska by the time Rearden hit eighth grade. His affection for the relationships and shared village culture – transmitted in stories -- only grew.

“I am a firm believer that all that was right with humanity up to 10,000 years ago was because of story. The way to be a human being. We have lost that.

“We don’t tell stories that are meaningful anymore, that people can learn how to be better people from. That’s why I am drawn to fiction, and I’ll try to do that.”

Therein lies a hint to the novel’s characters that he’s currently searching out. What voice will be the storyteller? And what role will a whale play?

The oldest mammals

Conceivably, says Rearden, a whale that spanned all three of these eras could still be swimming gracefully through the ocean. Some whales are commonly thought to live at least 100 years.

But in a 2001 column, science writer Ned Rozell cited research that proposed lifespans much longer than that. In,

“Bowhead Whales May be the Oldest Mammals,” scientists aged whales through chemicals in their eyes and from embedded ivory harpoons discovered by hunters. The oldest whale they studied could potentially have been 245 years old – a survivor through early indigenous whaling and the East Coast industrialized fleets of the 1800s.

|

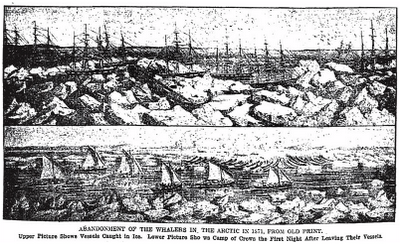

| Abandonment of the Whalers in the Arctic in 1871, from an old print. |

Then, questing after lucrative whale oil, whaling fleets ventured farther and farther north, until

September, 1871, when 32 of some 41 ships got stuck hard fast in the Arctic ice. More than 1,200 people survived, but the catastrophe -- and the simultaneous discovery of kerosene as an alternative fuel -- delivered a crippling blow to that whaling era.

Not lost to Rearden’s fertile imagination is the circling back to the Arctic that the current Beaufort and Chukchi Sea oil exploration means. The collapse of the fishing fleets of the 1800s coincided with the discovery of fossil fuels and the rapid industrialization of modern times.

Now that same enormous appetite for energy has brought us back to the home of the bowheads, home of that once sought-after lamp oil.

The draw for Rearden to a whaling novel includes a fascination for what science is currently learning about whales – their intelligence and the capacity some have for language and culture.

But there is more: the power of the whale in Alaska Native culture.

“Some of it just fascinates me,” Rearden says, “How story affects behavior. So, when it’s whaling season, everyone gets along in the village. There are no bad thoughts, no arguments, because the whale would be able to sense that. There are stories about that, and I’ll definitely work with that idea.”

The notion of an old whale that has survived both pre-contact and industrialized whaling, a whale that has lived that long and then allows itself to be taken in the third, subsistence era – “it’s because something was right about that,” Rearden says, “for the whale to give itself. “

Perhaps we are coming full circle, he thinks, “to where we advance enough that we have the understanding of whales that these ancient people did. Maybe we are regaining something that was lost.”

'There was an asterisk'

And finally, what about that question of hutzpah, a creative writer going after research funds from the INNOVATE awards.

Rearden smiles. “There was that asterisk on the application, and it said the research could be for creative works. And I thought, could I get that?” He decided to try.

But he also did it for his students. He teaches newcomers who need help with the writing process through the College Preparatory and Developmental Studies. He also teaches the novel

Ishmael by Daniel Quinn in the University Honors College.

And he sits on a committee that awards undergraduate research grants. Sometimes awards in the humanities go unasked for, and un-awarded. “I am always telling my students they really should apply, for their creative work. I couldn’t be a hypocrite myself, and not apply.”

To Rearden, his INNOVATE award signals that UAA, which prides itself in being a home for research, definitely casts its support to work in the creative arts.

________________________________________________________________

|

| Don Rearden |

Don Rearden is a new dad this year, father to young Atticus. His wife, Annette, is a professor in the School of Nursing. After his long stays in rural Alaska sharing and enjoying Native foods, he confesses a fondness for

Akutaq, Eskimo ice cream, and being an accomplished hunter of moose and caribou. He has worked at UAA seven years, and has his master's degree in Creative Writing. His first novel,

The Raven's Gift, was published in 2011.